It always starts quietly.

A word changes.

A tone shifts.

And suddenly, a country is no longer a country.

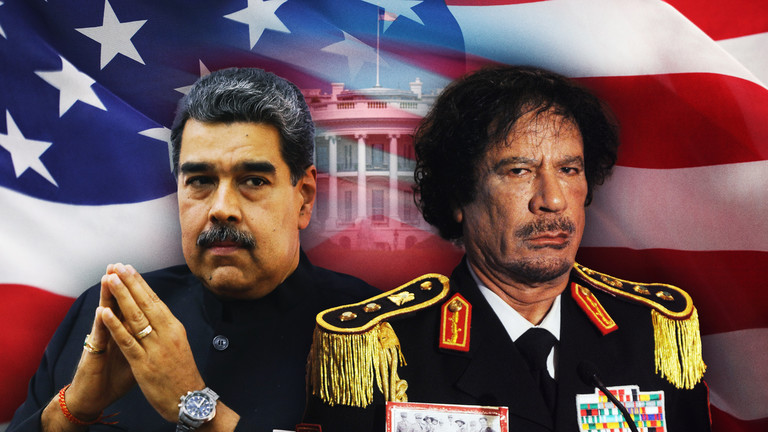

When US officials announced a multimillion-dollar bounty on Venezuela’s president, the language felt oddly theatrical. Less diplomacy, more frontier justice. A modern wanted poster, polished for prime time. The message was clear even if the wording was carefully scrubbed: this was no longer about politics. It was about a manhunt.

Western media played its role smoothly.

The proposed military raid was not framed as an invasion. It was a capture. Not a violation of sovereignty, but a law enforcement operation. A subtle distinction that carries enormous consequences. Once a head of state is described as a criminal suspect rather than a political leader, the rules change. International law fades into the background. Force becomes procedure.

This pattern is not new.

Help keep this independent voice alive and uncensored.

Buy us a coffee here -> Just Click on ME

For those who watched Libya unravel in 2011, the script is instantly recognizable. Muammar Gaddafi did not fall because tanks rolled in first. He fell because language did. One day he was a head of state. The next, he was declared illegitimate. Shortly after, he became a target. NATO bombs followed, but only after the media had finished its work.

Venezuela is being walked down the same corridor.

Before any talk of raids or arrests, the country was slowly rebranded. Not a sanctioned nation under economic siege, but a narco-state. Not a government struggling under pressure, but a cartel in suits. Once that framing takes hold, sovereignty no longer applies. You do not negotiate with cartels. You dismantle them.

That is the quiet power of words like capture.

To abduct a sitting president from his capital would be an act of war. To capture him sounds procedural. Almost boring. The media’s choice of language does not just report events. It pre-approves them.

This is perception management at its most refined.

In Libya, the same alchemy was performed. A complex political system was flattened into a single villain. Responsibility to Protect was invoked, not as a last resort, but as a moral shortcut. Bombing became humanitarian. Regime change became rescue. And the press followed obediently, reducing a sovereign state into a criminal enterprise that needed policing.

The result is visible today.

Libya is now described as a failed state, as if collapse were a natural disaster rather than a manufactured outcome. Its fragmentation is treated as unfortunate but inevitable. Rarely is it acknowledged that the media-assisted erosion of legitimacy came first, clearing the runway for destruction.

Venezuela has not yet reached that final stage, but the signals are unmistakable.

By the time bounties rise to cartoonish levels and officials speak like bounty hunters rather than diplomats, the legal groundwork has already been laid. The public has been conditioned to accept that this is justice, not aggression. Arrest, not invasion. Capture, not kidnapping.

This is how judicial language replaces diplomacy.

Courts substitute for negotiations. Indictments stand in for treaties. Domestic law is projected outward, turning the globe into a single jurisdiction where power decides guilt and the media plays bailiff. The United Nations, once meant to guard sovereignty, is left managing the wreckage after sovereignty has already been stripped away.

The deeper pattern is hard to ignore.

Before bombs fall, words do.

Before states collapse, they are renamed.

Before invasions begin, nations are turned into crime scenes.

If this disposability script continues to be accepted, then Libya was not an exception. It was a prototype. And Venezuela is not a crisis waiting to be solved, but a test of how far the language of capture can go before sovereignty disappears altogether.

When the law belongs to the strongest, and the media decides who counts as a criminal state, the world does not move toward order. It drifts into a permanent grey zone.

And in that zone, only the bounty hunters ever seem to win.